Images

Mice eat less when their hepatic glucose stores are high.

“We have to find treatments to increase hepatic glucose because of its positive effect in diabetes and obesity,” says Joan Guinovart, head of the study published in Diabetes.

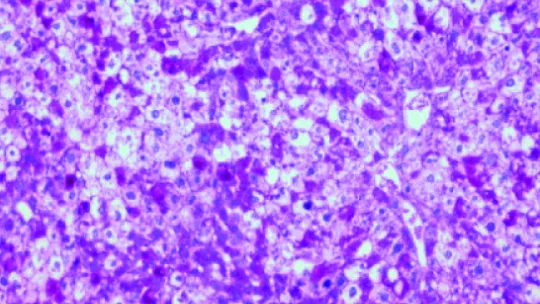

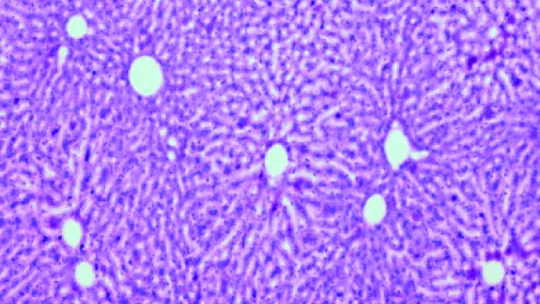

The liver stores excess glucose, sugar, in the form of glycogen—chains of glucose—, which is later released to cover body energy requirements. Diabetic patients do not accumulate glucose well in the liver and this is one of the reasons why they suffer from hyperglycemia, that is to say, their blood sugar levels are too high. A study headed by Joan J. Guinovart at the Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB Barcelona) demonstrates that high hepatic glucose stores in mice prevents weigh gain. The researchers observed that in spite of having free access to an appetizing diet, the animals’ appetite was reduced. This is the first time that a link has been observed between the liver and appetite.

On the basis of the results published in the journal Diabetes, the researchers argue that the stimulation of hepatic glycogen production would provide an efficient treatment to improve diabetes and obesity.

“It is interesting to observe that what happens in the liver has direct effects on appetite. Here we reveal what occurs at the molecular level,” explains Guinovart, head of one of the leading labs worldwide devoted to glycogen metabolism and associated diseases.

Tomorrow, November 14 is World Diabetes Day. The incidence of diabetes and obesity is rising. The World Health Organization estimates that 382 million people worldwide currently live with diabetes and for 2035 it forecasts that one in every 10 people will have this disease. With respect to obesity, which is closely associated with the onset of type 2 diabetes—the most common type of diabetes—the numbers are even higher. In 2008, more than 200 million men and around 300 million women were classified as obese.

“By understanding what doesn’t work properly in diabetes and obesity in the molecular level, we will be closer to proposing new therapeutic targets and to finding solutions,” explains Guinovart, although both diseases can be prevented by eating a balanced diet and exercising daily. “In the case of type 2 diabetes, with diet alone the numbers of people with this condition would half,” states Guinovart.

How do the liver and brain communicate with each other to regulate appetite?

The researchers questioned why mice that accumulated most glycogen in the liver did not gain weight in spite of having access to an appetising diet. In addition to observing that these animals ate less, the scientists found that the brains of these animals showed scarce appetite-stimulating molecules but rather many appetite-suppressing ones.

“Then we finally hit on the clue—with the signal that could explain the liver-brain connection,” explains Iliana López-Soldado, a postdoctoral researcher who has been working on these experiments for three years.

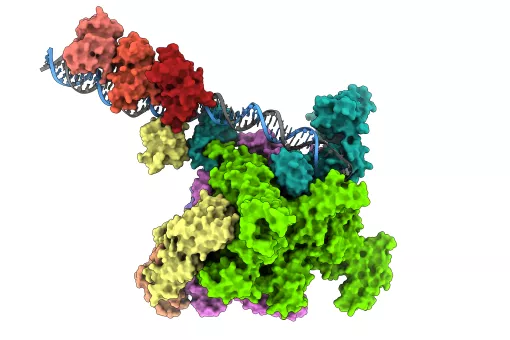

The key to the liver-brain link is ATP, the molecule used by all living organisms to provide cells with energy and which is commonly altered in diabetes and obesity. “We have seen that high levels of hepatic glycogen, stable levels of ATP, and high levels of appetite-suppressing molecules in the mouse brain are perfectly correlated,” explains López-Soldado.

This study has been funded by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad and by the CIBER de Diabetes y Enfermedades Metabólicas (CIBERDEM), a network to which the lab headed by Joan Guinovart—also senior professor at the University of Barcelona—belongs.

Reference article:

Liver glycogen reduces food intake and attenuates obesity in a high-fat diet fed mouse model

Iliana López-Soldado, Delia Zafra, Jordi Duran, Anna Adrover, Joaquim Calbó, Joan J. Guinovart

Diabetes. 2014 Oct 2. doi:10.2337/db14-0728

About IRB Barcelona

The Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB Barcelona) pursues a society free of disease. To this end, it conducts multidisciplinary research of excellence to cure cancer and other diseases linked to ageing. It establishes technology transfer agreements with the pharmaceutical industry and major hospitals to bring research results closer to society, and organises a range of science outreach activities to engage the public in an open dialogue. IRB Barcelona is an international centre that hosts 400 researchers and more than 30 nationalities. Recognised as a Severo Ochoa Centre of Excellence since 2011, IRB Barcelona is a CERCA centre and member of the Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology (BIST).